SWAMPSCOTT — These are the lessons Charlie Baker’s parents taught their three boys: Serve your community; when you’re knocked down, get right back up; learn from your mistakes.

On Thursday, when Baker is sworn in as the state’s 72d governor, it will be the culmination of a life and career in which he has tried to live out those lessons.

But there will be a hole in the proud family tableau arrayed around him.

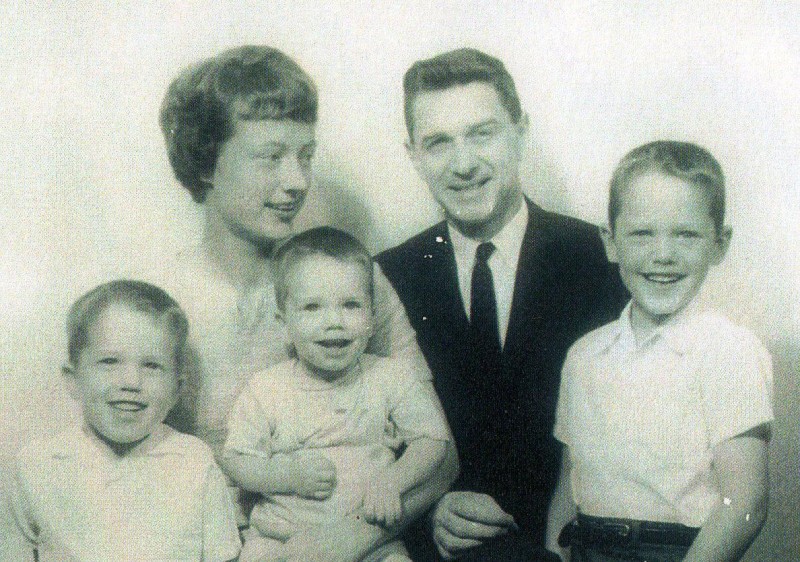

His father, also named Charlie, will be there to see the inauguration, beaming. His mother, Betty, will not. The once-vital, funny woman whose firm, loving hand shaped the younger Charlie Baker into someone who could win the state’s highest office doesn’t know her boy will finally be governor. Suspended in the cruel in-between of Alzheimer’s disease, she no longer knows him at all.

“I am my mother’s son,” Baker said, adding later: “She knew for a long time that this was something that was important to me. It’s hugely disappointing that she doesn’t know I took a second shot at it, and it worked.”

Betty Baker and her family always assumed she would get the disease. Alzheimer’s had picked off so many on her side of the family, it was hard to imagine she’d somehow be spared. They even joked about it sometimes.

Still, nothing quite prepares loved ones for that unmistakable beginning. She got lost in the mall more than once. At a celebration of her 50th wedding anniversary, she gave the same beautiful toast several times. She was starting to slip away.

Betty Baker was a lot to lose: a voracious reader and letter-writer, a Democrat happily married to a Republican, head of Christian education at a Congregational church, mother to dozens of children besides her own official three.

“Every kid at the neighborhood hung out at my house,” her son recalled, his eyes welling. “My mother used to buy cookies and soda when she went shopping, for literally 30 kids.” The Baker house on Cleveland Road in Needham was halfway to every place kids were headed. There were always armies of her sons’ friends around, and casseroles on the stove to feed them. She kept her kids in line not by yelling at them, but by making them dread the thought of disappointing her.

“I would describe her management style as firm, with a soft voice,” Baker said.

The soon-to-be governor’s parents — his father from a “classic New England family,” his mother a Midwesterner from Rochester, Minn. — were not the type to complain. When the disease descended, his father simply got down to the business of caring for his mother. She’d looked after her family for 40 years, the elder Charlie Baker would say. Now it was their turn to look after her.

In the early stages, his mother was dismayed by her decline, apologetic that she could no longer conjure the massive holiday feasts that had seemed effortless before. She also approached her disease with characteristically edgy humor.